A fictional account based on the tragic events at Coney Beach, Porthcawl, on April 1st 1994, thirty years ago today.

The metal hoop slices through the boy’s neck as, catching him under the chin, it catapults his whole body sixty feet upwards into an arc before landing the traumatized frame, dead, and, but for a bloody flap of connecting flesh, decapitated, onto the roof of a nearby beachside cafe, the vertebrae completely severed by the ferocity of the strike. Seconds before, sitting in the seats in front of him in the open carriage, his older brothers somehow find the lightning reflexes to duck as the gantry, festooned in light bulbs and fatigued after half a century of straddling the track, gives in to the gale buffeting it from the sea and collapses onto the path of the car hurtling the fifty-foot descent to the water splash below.

A split second of disbelief is broken by the screams of onlookers, some instinctively hiding the bewildered faces of children into their torsos, protecting their young from any understanding of what has just happened, and before any pictures of the butchery stick. Looking frantically to the seats behind them in the derailed car, the charmed teenagers see nothing of their sibling, only the bloodied heap of their mangled father, slumped unconscious across the double seat where their kid brother should have been.

This had been Dad’s treat, Mam deciding it was far too windy, far too cold (and, being Good Friday, faintly sacrilegious), to spend her bank holiday at the seaside. Not on the first day in April. She was no fool. They could have fun if they liked at this dress rehearsal for the real holiday season; she would wait until the summer. But the cold and the wind – up to one hundred miles an hour that day, they said later – did not put off her husband. He and the boys would have a great time with or without her.

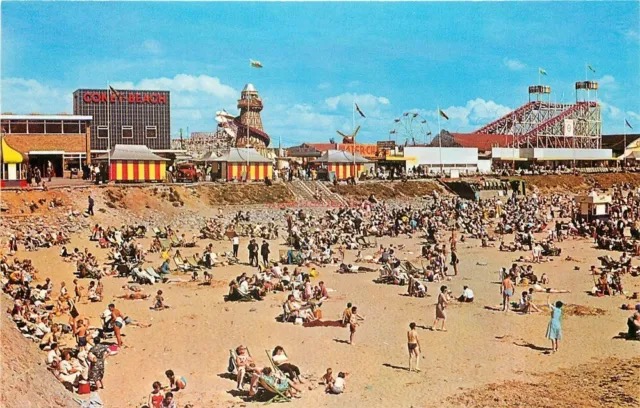

In truth, he had always been a bigger kid about the seaside than his own children. And if she’d heard him rattle on nostalgically about that particular place – and that ride – once, then she’d heard him talk about them a hundred times. How he and his brothers were only allowed to go to the fairground twice during their once-a-year week’s holiday, money not growing on trees; how the second visit was always the bittersweet finale of the week; the Friday night before the depressing leave-taking of caravan, sand, sea, doughnuts, toffee-apples, candy-floss, fish and chips, and, of course, the famous Water Chute.

How all week the cars on the tracks of the seaside town’s signature attraction had never been far from his mind, or sight, regardless of where he was playing on the beach or in the sea; how, over and over, he would watch, spellbound, as the brightly coloured buggies climbed the steep incline, slowly turning in the bend at the top before speeding down to the water waiting to drench their screaming occupants.

So often had his wife heard these reminiscences that, if she had been there herself, she couldn’t have pictured them more vividly. Like how, when he was about the same age as their youngest, he had stolen quietly out of the caravan with Grandad early in the morning, before the rest of the family were up, to take a stroll along the front and then around the empty fairground. How he had marvelled at the gaudy rides, quiet and still unlike their usual hurly-burly; waltzer, dodgems, chair-o-planes and many more, deserted now apart from the hands tightening bolts, greasing springs, adjusting levers. How he had gaped at the sight of the men walking the steep incline of his favourite’s tracks, goggle-eyed at how they showed no fear about the height and the exposure to the elements as they checked everything was in working order.

Yes, and she knew, because he had told her so many times, just how much wandering this dormant wonderland at that early hour felt like being in a secret world, open just to him and his grandfather, something almost as special as when everything burst into life a few hours later.

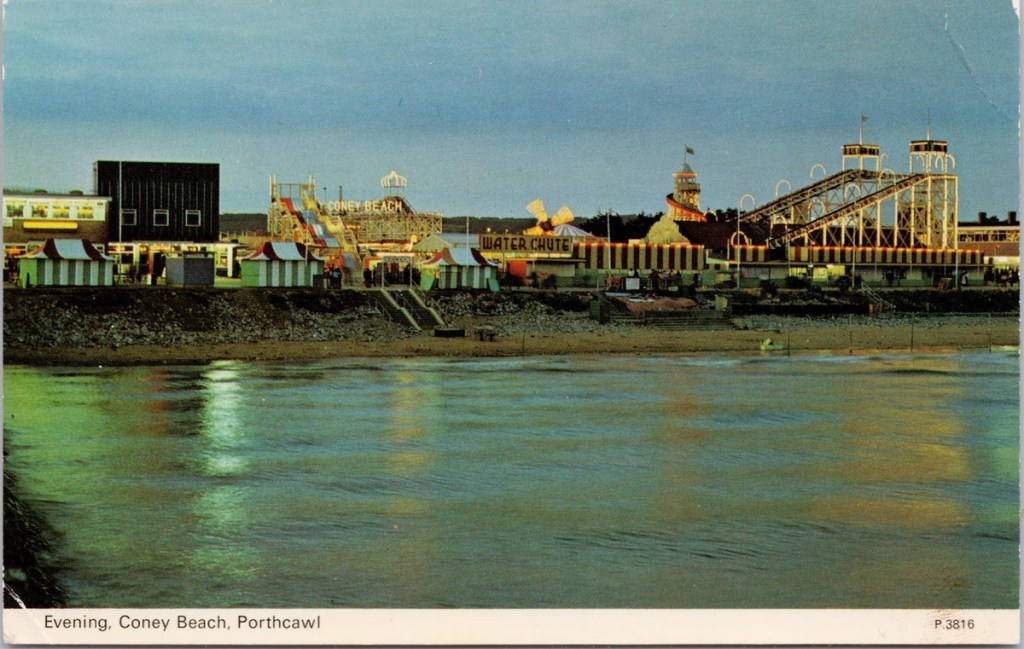

The woman knows also how this boy – whose children she will bear when he becomes an adult (though never quite fully a grown up) – put off until the end of that last night, the ride he loves best: when the sun had fallen enough for them to switch on the overhead arcs to illuminate its track: up, round and down.

She feels how he thrills, finally, when his turn comes, to stepping down into the seat next to his brother, handing over his fifty pence, the coin hot and damp with mixed terror and excitement; how with a sudden jolt forward, the underside motorized belt clanks him further and further away from the ground; how his heart thumps as the car inexorably climbs the track, his pulse quickening at the sight of the parallel metal lines on the other side waiting to take him to his stomach-turning fate, now only a few metres – and a few moments – away; how, at the summit, the point of no return long gone, the car calmly turns then suddenly dips in front of his eyes, accelerating downwards under its own momentum in an exhilarating but eerily quiet rush into the explosive hit of water below. Then, soaked amid shockwaves of adrenalin, hysteria and relief, the bonus treat, at the discounted price of twenty pence, to stay inside for another turn. A bargain, for a second go on the ride of his life.

* * *

Inquest over and health and safety executive report published, the engineers move in to take the fifty-year old structure apart; to remove for good the resort’s iconic seafront landmark, centre-stage for decades on postcards, tea-towels and placemats; the back-drop to endless photographs and memories. With the physical link to the thrills and spills of the past irrevocably severed, only dark folklore and pain remain: a horror story of an innocent cut down in a moment’s conspiracy of circumstance and metal fatigue, and an irreconcilability of memories tearing a grown man apart.

4 responses to “Fools’ Day”

Oh, I’ve just read up about Coney Beach. There were several incidents in 1994. What a tragic story.

LikeLike

I’ve melded fact with memoir. I had many holidays as a child at Porthcawl.

LikeLiked by 1 person

<

div dir=”ltr”>Not a pleasant story

LikeLike

Is that an observation (granted) or a criticism?

LikeLike